Venture capitalist and former music startup founder David Pakman has compiled some grim statistics on the survival rate of VC-backed music services. “Since 1997, according to PitchBook, approximately 175 digital music companies were created and funded by venture investors. Of those, approximately 33 were acquired by larger companies, often for less money than their investors put in,” he writes in a blog post on Medium, taken in part from testimony he gave last year before the Copyright Royalty Board. “Of those who have exited, I believe only seven achieved meaningful venture returns for their investors by returning more than $25 million in profit to their investors (Last.FM, Spinner, MP3.com, Gracenote, Thumbplay, Pandora and possibly The Echo Nest), representing an investor success rate of only approximately 4%, far below that of other internet and technology market segments.

Venture capitalist and former music startup founder David Pakman has compiled some grim statistics on the survival rate of VC-backed music services. “Since 1997, according to PitchBook, approximately 175 digital music companies were created and funded by venture investors. Of those, approximately 33 were acquired by larger companies, often for less money than their investors put in,” he writes in a blog post on Medium, taken in part from testimony he gave last year before the Copyright Royalty Board. “Of those who have exited, I believe only seven achieved meaningful venture returns for their investors by returning more than $25 million in profit to their investors (Last.FM, Spinner, MP3.com, Gracenote, Thumbplay, Pandora and possibly The Echo Nest), representing an investor success rate of only approximately 4%, far below that of other internet and technology market segments.

Only two have achieved an IPO, and at least 15 companies have resulted in a distressed exit and/or filed for bankruptcy so far, for an 8.6% failure rate to date.”

Music business and technology consultant Andy Edwards offers a similarly dire analysis in a post on Music Business Worldwide, concluding that only one fully licensed music startup has managed a successful exit since 2004, and that was Last.fm, which only became fully licensed ahead of its $280m sale to CBS in 2007.

Both Pakman and Edwards puts the blame for that grim toll squarely on onerous licensing demands of the major record companies.

According to Edwards, those demands have generally imposed much greater fund-raising requirements on music startups compared with consumer-facing startups in other technology sectors, creating difficult economics at the outset.

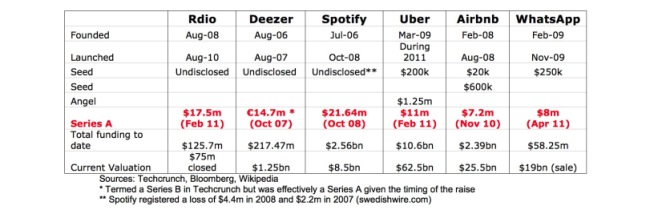

“Rdio, Deezer and Spotify required a Series A funding round that was more or less double [sic] the Series A for three of the most successful start-ups of recent times,” he writes. “Spotify is by far the most successful music tech start-up in terms of scale and impact. It was founded in 2006, launched in late 2009 with a Series A of $21.6m. On this funding round Spotify concluded deals with all three majors and Merlin. Reports suggest the company burned through $8m prior to the Series A, so Spotify was $30m in the hole pre-launch.”

Pakman is more blunt.

“I am unaware of any standalone digital music company or webcaster who has achieved profitability. This is a direct result of the high royalty rates required by startups who wish to license digital music for use in their apps,” he argues. “Whether you negotiate voluntary agreements or avail yourself of the existing compulsory licenses, you will not turn a profit. At least, no one ever has…The end result of these perilous market conditions is that the only companies who can afford to be involved with digital music are the internet giants prepared to subsidize their digital music services with profits from their other businesses. The high royalty rates and up-front cash advances required by the record companies prevent profitable, sustainable businesses from emerging. As a result, the recorded music businesses is left only with these giants — Amazon, Apple, and YouTube and, to a lesser extent, Spotify and Pandora.”

The case isn’t a new one, but it’s cogently put by both Pakman Edwards, and their arguments are admirably supported by actual data. Yet the data they cite could also be read to illustrate the skewed investment priorities within the music business generally, whether coming from venture capital sources or players within the industry itself.

All of the startups Pakman and Edwards analyze are (or were) consumer-facing service providers, selling, renting or otherwise providing music directly to listeners. And indeed, that’s where most of the investment has gone in the music business for the past decade or more. Comparatively little investment has gone into developing the infrastructure for capturing value from music apart from the traditional methods of direct payment or advertising sales, and where it has it has often ended up being diverted to more traditional applications.

SoundCloud is a case in point. It began with the goal to become the audio platform for the web and was embraced by many up-and-coming musicians and EDM artists as a way to gain exposure and share music directly with their fans via Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and other social media outlets, attracting significant investment capital along the way. It also, of course, became a popular place for sharing unlicensed music, drawing the legal ire of the labels and publishers.

Instead of investing in SoundCloud’s potential as a platform for working musicians the labels and publishers demanded it become a licensed streaming service, which it now has with the launch of SoundCloud Go.

Instead of becoming a vendor to the industry, in other words, SoundCloud has become another customer to the labels and publishers, and will face the same difficult economics that other streaming services face.

That pattern is not confined to the music industry. In many media sectors, investment to date has focused largely on consumer-facing applications, rather than value-capturing infrastructure.

Investment priorities are starting to change, however. In the music business, Dubset has developed technology to analyze DJ mixes and EDM mashups to identify their constituent tracks and map those data to the appropriate rights owners. As a result, content that previously would have been distributed without a license can now be sold and streamed by commercial services under license. Value that previously was given away can now be captured.

ClearTracks, currently in beta, aims to build a payment processing system for the music industry modeled on the MasterCard and Visa networks. The goal, according to founder Danny Anders, is to create the infrastructure to enable innovation at the edges of the music ecosystem by providing an open payment system for both merchants and providers.

New York-based startup Monegraph is leveraging blockchain to establish provenance for digital photographs and artwork to enable trusted commerce in digital works where none existed before.

You can hear from all three companies and many more about the emerging technologies for capturing value on digital platforms at the inaugural RightsTech Summit in New York in July. Click here for information on how to register.